LLMs Have No Memory of Time

Ask Claude what day it is and it’ll tell you. Ask it whether the thing it read five minutes ago is newer than the thing it read an hour ago, and it has no idea.

This isn’t a bug. It’s a fundamental property of how LLMs work. Everything in the context window is equally “now.” There’s no before and after. No newer and older. A claim from January 2025 and a claim from February 2026 sit side by side in the context, and the model treats them as equally current.

I’ve been running a multi-agent AI research programme — six AI agents across seven repositories — and this one property caused more problems than anything else.

What Goes Wrong

When you give an AI agent a role definition file (I use CLAUDE.md), that file becomes ground truth. The agent reads it, believes it, and acts on it. The problem: the file doesn’t know when it was last updated. Neither does the agent.

I ran an audit of all six role definition files in my research programme. Every single one was stale:

- The physics repo’s README said “the framework hasn’t derived the inverse-square law” — but an entry from three days earlier showed it had

- The reviewer’s role definition didn’t mention breakthroughs from the physics repo made the same week

- The PI’s own file contradicted its own entries — the tensor sector was marked “resolved” in the role definition but classified as “falsified” in an entry from the same repo

Six files. Six agents. All operating on outdated beliefs. None of them knew it.

This is what happens when you build a system with no sense of time.

The Classical AI Version of This Problem

It turns out this isn’t a new problem. In 1969, McCarthy and Hayes identified what they called the frame problem: how does a reasoning system know what changes when something happens, and what stays the same?

The practical compromise is called the sleeping dog strategy — assume everything stays the same unless you explicitly change it. It works most of the time. When it fails, there’s no detection mechanism. The dog sleeps through changes it should have noticed.

That’s exactly what my agents were doing. They assumed their role definitions were current. Nobody woke the sleeping dogs.

The belief revision literature (Alchourrón, Gärdenfors, and Makinson, 1985) makes a useful distinction: revision is updating beliefs because you got new information about a static world. Update is changing beliefs because the world itself changed. A role definition going stale because the research moved forward is an update problem, not a revision problem. They require different operations. My agents had neither.

The Fix: Encode Time in the Filesystem

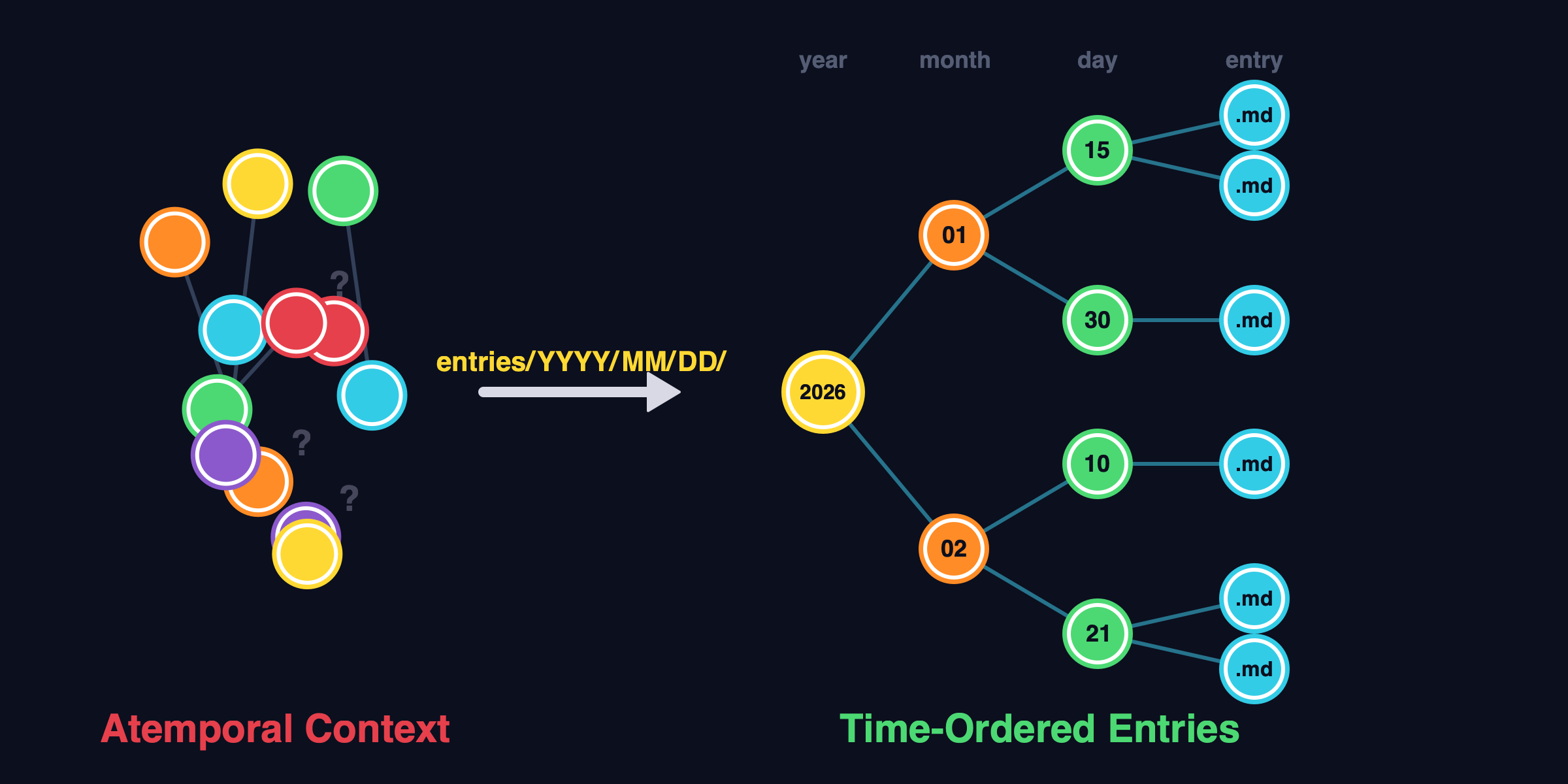

The solution I landed on is embarrassingly simple: put the date in the directory path.

entries/

2026/

01/

30/

memory-limitations.md

ai-as-stakeholder.md

02/

21/

belief-reconciliation.md

sawtooth-compaction.md

22/

cascading-belief-failure.md

Every entry lives at entries/YYYY/MM/DD/filename.md. The path is the timestamp. An agent reading the filesystem can see that entries/2026/02/22/ is newer than entries/2026/02/21/ without parsing any content. Time ordering is structural, not semantic.

This works because agents read paths structurally but read content atemporally. Put a date inside the file and the agent treats it as text. Put the date in the path and it’s part of the navigation structure.

I built a small CLI tool called entry to enforce this:

$ entry create "Investigation into belief staleness"

Created: entries/2026/02/22/investigation-into-belief-staleness.md

Three things happen automatically:

- The date directory gets created from today’s date

- The title gets slugified (no spaces — agents love creating filenames with spaces, which breaks everything downstream)

- A standardized template gets filled in (Date, Time, Overview, Details, Next Steps, Related)

Why Not Just Use Timestamps in Files?

I tried that first. It doesn’t work.

When an AI agent reads a file that says **Date:** 2026-01-15 at the top, it processes that as text content, not as temporal metadata. The model has no mechanism to compare that date against another file’s date and conclude “this one is newer.” It can do the comparison if you explicitly ask, but it doesn’t do it automatically when deciding what to believe.

Directory paths are different. When an agent lists files or navigates a filesystem, the path structure is part of how it locates information. An agent looking at entries/2026/02/22/ and entries/2026/01/15/ processes the path hierarchy as navigation — and navigation has inherent ordering.

The directory structure also makes git log, ls, and find work naturally. You don’t need special tooling to answer “what happened last week?” — it’s just ls entries/2026/02/15/ through entries/2026/02/22/.

The Right Time Unit Depends on the Domain

Calendar days work for research journals, project logs, and meeting notes. But I also tested this on an automated software development pipeline that runs in minutes, not days. All the entries landed in a single day directory — useless.

The fix: use the right temporal unit for the domain.

- Research programmes: calendar days (

entries/YYYY/MM/DD/) - SDLC pipelines: iteration numbers (

entries/iteration-1/,entries/iteration-2/) - CI systems: build numbers (

entries/build-42/,entries/build-43/)

The principle — impose temporal structure externally because the model can’t maintain it internally — is constant. The granularity varies.

An Unexpected Finding: Entries as Specs

Something I didn’t design for: entries turned out to work as cross-session coordination artifacts.

In one case, I wrote a to-do list as an entry with six prioritized items for improving an automated SDLC pipeline. I committed it to git. A separate Claude session — with zero shared context, no conversation history, no handoff — read the entry and implemented all six items in 67 minutes. 371 lines of code. Plus a follow-up bugfix for an edge case the spec didn’t mention.

The entry worked as a spec because it had:

- Specific file and line references (the agent didn’t need to explore)

- Concrete examples (verdict block format, exit gate logic, prompt text)

- Priority ordering matching natural implementation order

- Rationale explaining why, not just what

Two sessions coordinated on a 371-line change through a single markdown file in a date-organized directory. No shared context, no handoff meeting. The filesystem was the coordination mechanism.

What I Learned

After hundreds of commits across 7 repositories:

-

Models don’t have time. You have to give it to them. Timestamps in file content are decoration. Timestamps in directory structure are functional.

-

Stale beliefs are the silent killer. Nobody notices when a role definition goes stale. The agent keeps working confidently on outdated information. An audit found 100% of role definitions had staleness issues.

-

The right time unit matters. Calendar days for humans. Iterations for pipelines. Build numbers for CI. Match the granularity to the workflow.

-

Entries are more than documentation. They’re coordination artifacts, specs, audit trails, and temporal anchors. Once you have time-ordered records that agents can navigate structurally, they find uses you didn’t plan for.

Try It

# Install

uvx entry install-skill # teaches Claude about the tool

uvx entry init # creates entries/ directory

# Use

uvx entry create "My first entry"

Or just create the entries/YYYY/MM/DD/ directories yourself. The tool enforces conventions but the principle works with any filesystem.

The code is at github.com/benthomasson/entry. Zero dependencies. Three commands.

This is the first in a series on belief management for AI agents, based on a year-long multi-agent research programme. Next up: what happens when your agents start disagreeing with each other — and neither of them knows it.